Article begins

There is a way that we exist among ourselves, nestled securely into our knowing, oyster knives in hand.

The following vignettes serve to provide a glimpse into what I have been doing in this space as a Black woman and graduate student of anthropology. A series of scenes from my preliminary fieldwork with a community of healers in Brooklyn, New York, and a church in South Bend, Indiana, as well as those of the everyday illustrate the sensory matrix of my experience and begin to answer the question of what it means for me to reside here. This is my invitation for you to come on in for a spell.

What is it like? How does it feel? How’s that going for you? I bet that’s…

It feels like I’ve been off studying all this time and still can’t spell the clucking sound. But it also feels like perhaps I once could, and now I am performing a dance between alienation and re-membering. Thus, it feels quite urgent and rather precarious, but also wonderfully free from the claustrophobic parameters of empiricism as we know it—both scripted and improvisational.

It tastes like a tea blend steeped in hot water for seven minutes with a few drops of herbal oil, for focus. The folks at the Brooklyn wellness space swear by it and insist that it will help me concentrate on my writing and relieve any of my anxieties. We sip and ponder: You know, I’ve never met a Black anthropologist before, but it’s been fun having you around. We sip and chat: Oh, and I can’t wait to read your article. Feel free to use my name, first and last! We sip in silence.

It looks queer. Like an essay that answers the archaeological canon with urban street photography as maps, commentary on gentrification, and writings on affect and queer place-making, all grounded by the voices of local organizers and animated by works of literary fiction. It looks like a syllabus without a designated “women” or “indigenous” or “black” or “of color” week because they’re present throughout. It also looks like a tarot spread, arranged in an arch-like fashion as my interlocutor and card reader sits across from me insisting that what I am doing as a researcher and “witness” is also healing work—just look at the story the cards are telling. It looks as though I too am queer, ethnographer and witness and healer and, and, and.

It smells like clustered bodies on the subway and fumes from my multicolored ink pen as I scribble field notes like:

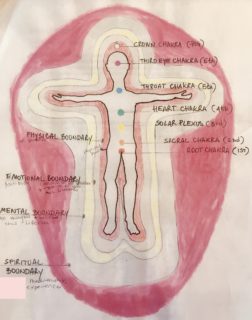

I asked her the difference between feeling and sensing. She used her diagram of the energetic body to demonstrate that our auras are passively taking in the energies that surround us. This is feeling. But we can control the boundaries of our auras through the intentional practice of sensing—negotiating our relationships to places and people.

Diagram of the energetic body. Drawing by Manu Del Prete and Nelly Reznik.

It smells like the difference between the Caribbean spice-riddled air of Flatbush Avenue and the increasingly intense smell of coffee coming from the store-front cafés as you travel up to Prospect Park—like if double-consciousness had a smell, like an olfactory code-switch.

It sounds like church announcements on my last day before a stint of fieldwork. “Sis. Symone is going off to do more research this summer in New York; please everyone come up to the altar.” It sounds like the hum of affirmative amens as the pastor prays over me that I have safe travels. It sounds like whispered personal prayers as a circle of believers stretch out their hands toward me. It sounds like well-wishes from the elders.

This particular lot in the break is the place upon which I build my house. Like any host before an expected guest arrives, I spent a great deal of time cleaning and prepping and rearranging to make it appear livable. However, it is in fact not perfectly neat or clean at all and so I will not perform neatness or cleanliness here; it is actually quite lived in and hence shows the wear of many decades of work. In this house is a collection of smells and tastes and sounds and feelings and images that have no definite form in and of themselves but are ordered and translated to knowing in the way myself, my contemporaries, and those before us have always simultaneously sensed and made sense of through dialogue with others who live here and those who are frequent visitors. This is the work. This is how it feels for me as a Black woman in anthropology. This the break.

Symone A. Johnson is a PhD student in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Notre Dame. Her research explores vernacular forms of healing as everyday liberatory practices of Black American futurity.

We welcome contributions to this column from ABA members! They can be submitted to ABA contributing editors Michelle Munyikwa ([email protected]) and Amelia Herbert ([email protected]) for review.

Cite as: Johnson, Symone. 2018. “Upon This Break, I Build My House.” Anthropology News website, December 12, 2018. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1056