Article begins

“A refugee is someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war or violence. A refugee has a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group.” UN Refugee Agency

Quetzaltenango is full of ghosts.

The Guatemalan city known as Xela (shey-la) bustles with the entrepreneurial projects of its roughly 200,000 residents. Indigenous and non-indigenous women sell meals at makeshift eateries from their street-level garages. Lawyers push papers from small offices, dozens of which are concentrated close to the city’s historic center. Global fast food chains commandeer the best buildings in key plazas.

Handwritten, painted, or printed signs by the doorways communicate each living business’s name. Yet, the walls lining the city’s cobblestone streets are also full of entrepreneurial ghosts. These are the ruins of modernity and capitalism that haunt many places. The “visible materiality” unassumingly holds the past ever present, like the hum of a generator to which few ears actively attend.

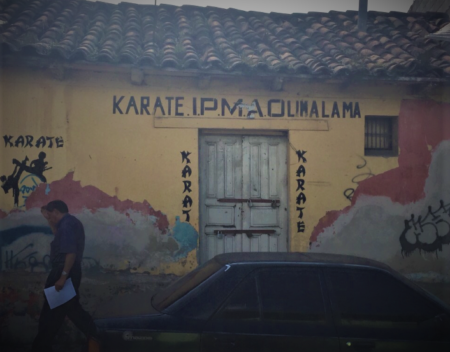

Some remnants of dead ventures remain for years. There’s the closed-down karate studio, whose art haunts what looks to be an abandoned building.

A closed karate studio in Xela, Guatemala. Ioulia Fenton

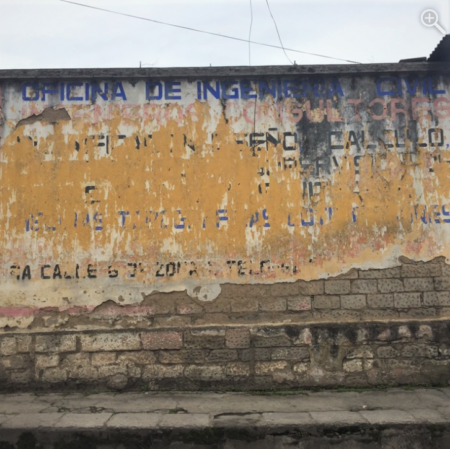

Across the street, the old paint of a perished engineering office slowly peels away along with the cement coating of a decaying stone partition.

A sign for a long abandoned engineering’s office. Ioulia Fenton

Doña Juana’s restaurant sign hangs on, although she has not hung around.

The sign remains but the proprietor is gone and the restaurant closed. Ioulia Fenton

Other remnants coexist alongside new economic projects, like a notary public’s advertisement beneath an e-cigarette business.

The sign for a shuttered lawyer’s office competes for space with signs for a new e-cigarette stop. Ioulia Fenton

Others are in the process of moving on to make way for the living. An independent taco joint lingers beneath a fresh coat of paint where it is rumored a new franchise of Pollo Granjero will be located.

The ghostly image of an out-of-business taco restaurant. Ioulia Fenton

Pollo Granjero is a popular fried-chicken takeout chain. The brand belongs to the Gutiérrezes, the most powerful of all the Guatemalan oligarchical families. They are among the 260 Guatemalan millionaires whose combined wealth amounts to 56 percent of the country’s GDP. Guatemala’s economic elites like them get to line their pockets from the country’s status as “a solid economic performer,” while more than 10 million of their fellow countrymen, women, and children struggle below the poverty line.

These buildings and markings are apparitions of dreams unattained, efforts curtailed, investments lost. At least some of the dreamers abandoned their country as well as their signs. Even some of the Gutiérrezes have moved to North America. Well over a million Guatemalans reside in the United States today, many are undocumented. Last year, they sent back $9.3 billion for the 16 million who remain. That is equivalent to 12 percent of the Central American country’s GDP.

As the opening UNHCR quote suggests, the world’s legal systems separate out those who flee threats of physical violence based on belonging to a marked group from those who flee economic peril. The former can seek asylum and refugee status. The latter cannot.

According to that definition, most Guatemalans who cross borders are migrants, not refugees. That is because they seek to escape poverty through jobs. Yet, the lines between political refugee and economic migrant are not clear cut in Guatemala. They blur and their blurring reveals additional ghostly and ghastly features of local markets. These features turn many Guatemalans, not simply into economic migrants, but into economic refugees.

Pedro sells fish and seafood products in a municipal market. He was kidnapped along with his brother when making their way home one night. The kidnappers demanded a ransom for their release. He hushed his voice when recounting the experience to me in 2011: “It was terrible and we were beaten badly. We couldn’t go to the police, we had to sort it out in the family. We took a loan to pay the Q100,000 [$14,000] release fee. This happens a lot in Guatemala because people are always watching and know our business. People get jealous when others do well.”

Pedro’s kidnapping was not unique then. Many people described criminal activity as destroying their livelihoods. With no other choices, they re-started businesses from scratch, sometimes becoming heavily indebted to predatory lenders of crisis funds. Some broke down in tears describing the trauma. They felt like ghosts of their former selves.

While gangs operating out of Guatemala’s notoriously ineffective prisons continue to be the suspected culprits, extortion has become a copycat game utilized by other criminals. You never know if the threat is real, business owners told me. It could be the gangs. But it could also be isolated groups whose occasional arrests made the front pages of the country’s dailies. Photos circulated in newsprint of the detained young men and women, shoulders hunched, arms handcuffed. They seemed like desperate people piggy-backing off Guatemala’s climate of fear and criminal impunity.

Juana, Pedro, and Alex’s entrepreneurial efforts illustrate just how hard Guatemalans work to start and maintain businesses. The apparitions on Xela’s buildings invite us to ask questions about why so many commercial efforts die in a country like Guatemala, the source of so many economic migrants to the United States. Enterprises perish but do not leave behind a cemetery that would denote a special place of burial or remembrance. Instead, they linger among those still living with their unfinished business. Perhaps they can escape purgatory when their stories are heard?

In some places, mushrooms can spring from lost forests, pointing to the “possibility of life in capitalist ruins.” In Xela, some new businesses spring up in place of defunct ones. But, too many empty shells linger abandoned, pointing to the impossibility of local livelihood after economic ruin.

The United States’ neighboring southern countries—the sources of its migrants—are not sending their “unwanted.” If the ghosts of Xela have any message at all, it is that many people making perilous journeys in search of economic opportunity have worked hard at opening their businesses and providing others with jobs. Rich or poor, local or foreign, they are members of an entrepreneurial class. They hold membership in a particular social group that faces persecution in the oft-linked processes of physical and economic violence. They can lose everything just when they start succeeding. They are persecuted, as Pedro said, as soon as they seem to do well. Newspapers confirm that the fear of the persecution is well founded. Seen as members of a persecuted entrepreneurial group, they meet the UNHCR definition of refugees.

Guatemalan economic migrants do not flee poverty resulting only from lack of opportunity or poor pay. They flee the extortion of their lives as soon as they make ends meet. That extortion is always economically violent. It is frequently physically violent too. Their businesses lie in visible ruins, pointing to the impossibility of livelihood in violent economies. Xela’s past and living ghosts push us to consider that our legal definitions need revisiting. Violent ghost economies make entrepreneurial refugees, not economic migrants.

Ioulia Fenton is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Anthropology at Emory University. She studies the impacts of multiple axes of precarity on Guatemala’s agri-food systems.

Walter E. Little ([email protected]) is contributing editor for the Society for Economic Anthropology’s section news column.

Cite as: Fenton, Ioulia. 2019. “Violent Ghost Economies Make Refugees out of Guatemalan Entrepreneurs.” Anthropology News website, December 20, 2019. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1333