Article begins

A museum display shares anthropological findings with the public.

As any pastoralist knows, managing livestock is challenging, particularly in an environment where droughts are common, diseases spread rapidly, and theft is always a possibility. We recently observed four herders as they passed the years together. In the first year, things began well enough, with three of them gaining livestock and only one suffering a loss. The unlucky herder asked his friends for help to keep his herds at a viable level for survival, and they shared animals with him. The next year, a drought struck, and three of the herds were in danger. But the fourth herder was able to bail them out, and they all made it to the next year.

© Exploratorium, exploratorium.edu

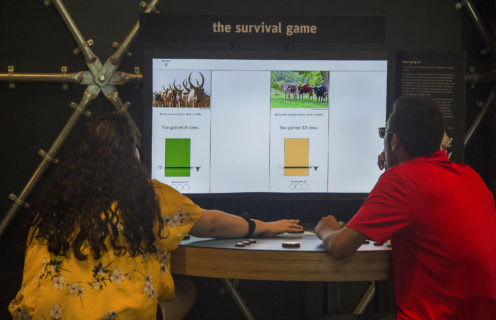

And so it went, until the pastoralists decided to move on to a different display in the Exploratorium, San Francisco’s hands-on science museum. The pastoralism we had been observing was virtual: museum visitors were playing The Survival Game, an interactive display based on our research among Maasai pastoralists. We designed this game with Exploratorium staff to teach museum visitors about interdependence and mutual aid in small-scale societies. In today’s individualistic and increasingly factionalized society, interdependence is not always understood or appreciated. The goal of The Survival Game is to encourage Exploratorium visitors to think about the ways in which they depend upon others and others depend upon them.

Our interest in interdependence began a few years ago with a study of osotua, a system of mutual aid among Maasai pastoralists in Kenya and Tanzania. Osotua literally means “umbilical cord,” but Maasai use the term metaphorically to refer to a kind of friendship based on mutual obligations: request help only if you genuinely need it, give it if you are able to do so without jeopardizing your own security, and do not expect anything in return. Because livestock are so important to the Maasai economy, most gifts are cattle, goats, and sheep, but any sort of gift or favor might be given from one osotua partner to another, if need be.

While playing the game, visitors learn that when you are interdependent with others for survival, helping others is in everyone’s long term best interests.

In 2014, we assembled a team to look at cooperation in societies around the world. The Human Generosity Project has explored risk-pooling and other forms of interdependence among Fijians; Mongolian herders; US ranchers; Hadza foragers; rural Appalachians; and Karimojong, Tepeth, and Ik communities in Uganda.

In Fiji, the principle of kerekere obligates Fijians to help fellow Fijians when they are in need. Because of the occasional cyclone, entire villages are sometimes in need, in which case they may kerekere a nearby village that was less affected by the storm. Human Generosity Project team member Matthew Gervais has been studying how relationships among villages are maintained through rituals in which symbolic objects are exchanged. One of the most notable of these objects is the tabua, a sperm whale tooth and a cord. The weight of the tooth symbolizes the responsibility of the relationship while the cord represents the relationship itself.

In the early days of The Human Generosity Project, one anonymous reviewer made the observation that we were studying societies in which people were known to be generous, and suggested, Why not also study a society where people are supposed to be selfish? This comment led us to northeast Uganda where, as many more senior anthropologists will surely remember, the Ik were made famous—or perhaps infamous—by Colin Turnbull’s ethnography The Mountain People, published in 1972. Turnbull described the Ik as “the loveless people,” a group so selfish and mean that, he argued, they should be divided and dispersed across Uganda so that their culture would cease to exist.

Human Generosity Project team member Cathryn Townsend spent 2016 conducting fieldwork with the Ik, and she found that far from being selfish, the Ik have a strong ethic of sharing, especially with those in need. A belief in earth spirits called kijawikå that are said to monitor behavior and then punish the selfish and reward the generous, reinforce their ethic of sharing. Turnbull’s findings appear to be a result of the fact that he observed the Ik while they were in the midst of a severe famine. Because everyone was starving, no one was in a position to help anyone else and the system of interdependence could not be maintained.

© Exploratorium, exploratorium.edu

Examples of interdependence are also found among ranchers in Arizona and New Mexico. They routinely help each other in a system they refer to as “neighboring” or “trading work.” People with the skills necessary to run a ranch are in short supply, and because the population density is very low, there few people available to provide help. But ranchers can be confident that their neighbors are sufficiently skilled to get the work done while (mostly) avoiding injuries.

We found that aid among the ranchers takes two distinct forms. When ranchers need help with routine, predictable chores, such as rounding up livestock for branding or marketing, they make arrangements to swap labor. In this situation, most ranchers expect that their help will be repaid in kind. But when needs arise at unpredictable times, as in the cases of injuries, illnesses, and sometimes deaths, no repayment is expected for help that is given, just as in the Maasai osotua system. Because ranching can be dangerous work, this system of mutual aid is an important safety net. In the words of one rancher, “If there’s any major occurrence that happens, these little communities all come together to take care of those left behind, clean their houses, feed them, really amazing.”

The ranchers show that an understanding of interdependence and the value of mutual aid exists in the United States despite the fact that the majority of the US economy is based on acquisition, accumulation, credit, debt, and repayment, rather than on sharing. At the same time, sharing with those in need is also part of life in the United States. Overall, about two-thirds of US households contribute to charities, which in 2014 added up to $258 billion. When a disaster strikes one region, Americans donate to the Red Cross and other charities. Ranchers donate surplus hay to ranchers in regions struck by drought. When Hurricane Harvey hit Houston, the Cajun Navy, a group of volunteers from Louisiana, came to the rescue, rescuing thousands of people from their flooded homes. More local needs inspire donations to food pantries and prompts volunteering to help meet those needs. Our laboratory and online experiments with participants in the United States confirm that when they play a version of the Survival Game and have to manage a herd of cattle in the face of potential disasters, they spontaneously help those in need without expecting to be repaid. The logic of interdependence is easy to understand and act upon.

The Survival Game strikes a chord with visitors because it appeals to something fundamental in human nature. Most exhibits at the Exploratorium hold visitors’ attention for only a minute or two, but groups of two to four visitors have been observed playing The Survival Game for five, ten, twenty, and sometimes even thirty minutes. While playing the game, visitors learn that when you are interdependent with others for survival, helping others is in everyone’s long term best interests. This shows in some of the things that museum personnel have overheard visitors saying while playing the game: “If we die, we die together!”; “If you give me five more, we are all ok”; “Oh no, Nana is really in trouble”; “Oh no, mommy. I’ll give you some”; and, finally, our favorite, from an English girl of about seven or eight: “Daddy, come play this really fun game!”

In modern, western and market-driven contexts, interdependence is not often recognized, acknowledged or appreciated. Daily life affords many the illusion of being independent—that we don’t depend on others deeply—because many needs are met automatically or by “interchangeable” individuals, such as the driver of the truck that delivers fruits and vegetables to the store so you can purchase them. But this belies the reality of a complex and extremely interdependent set of social, political, and economic systems in our neighborhoods, our cities, our countries and across the globe. Perhaps a better understanding and appreciation of interdependence would help many to better manage risks. Because, in the end, we are all playing the survival game together, whether we realize it or not.

Lee Cronk is a professor of anthropology at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, NJ.

Athena Aktipis is an assistant professor of psychology at Arizona State University in Tempe.

Cite as: Cronk, Lee, and Athena Aktipis. 2019. “Virtual Cattle and Actual Friends.” Anthropology News website, March 12, 2019. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1115