Article begins

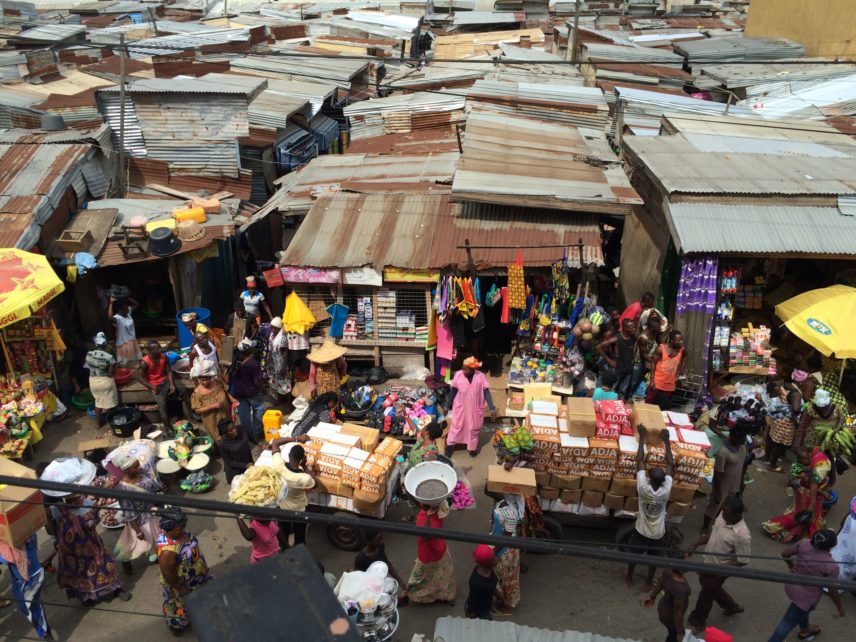

In the yam yard, wholesale traders bargain with traveling yam traders over large stacks of tubers just hauled in from the farm. Head porters weave through foot traffic with basins heaped with yams or boxes of canned goods balanced on their heads. Men who transport goods on three-wheel trucks or flatbed carts yell “Agoo!” to alert people to clear the path as they strain under their heavy loads. Along the perimeter of the market, vegetable sellers group tomatoes, onions, and garden eggs (small eggplants) into various price piles. Deeper into the market, the smell of burning charcoal and exhaust fumes give way to the aroma of ripe slabs of butchered meat, tomatoes warmed by sunlight and humidity, and the pungent odor of spray-painted aluminum cookware. Over in the secondhand clothing section, sellers rhythmically clap their hands and announce the price of their goods to attract the attention of passersby: “Nika, two! Nika, two! Ɛyɛ two Gaana!” (Shorts, two! Shorts, two! It’s two Ghana [cedis]!). Sellers of all goods call out to potential buyers; buyers visit their regular customers or subtly scan desired items to avoid locking eyes with any particular seller. Transactional exchanges commence, often with subtle nods, averted eyes, and discrete exchanges of cash.

Situated in Kumasi, Ghana’s second most populous city, is one of the largest open-air markets in West Africa. A sensory-rich space in which women are the primary traders, the Kumasi Central Market (KCM) is, and has historically been, a hub of exchange and distribution, attracting wholesalers and shoppers across coastal West Africa. On any given day, thousands of buyers and sellers engage in wholesale and retail trading activities—everything from foodstuffs to new and used clothing, textiles, electronics, household goods, locally crafted products, and services.

Talk in the form of face-to-face interactions drives these transactional exchanges, as captured in a common phrase, “Yɛde yɛn ano di dwa” (We use our mouths [our words] to trade). As a senior cloth seller told me, “Our work is about talking. If you don’t like talking, you can’t trade.” Through talk, market women negotiate sales, glean pertinent price and supply information, and manage customer relationships. They also exchange gossip (nkɔnkɔnsa)—which traders to trust or avoid, who has quality goods, who reliably pays their debts. In the KCM, exchanging gossip serves an essential economic function: it provides traders with access to important information about where they should direct their limited resources in an erratic marketplace.

Risky business

In the trading profession, often characterized as an income-generating activity in the “informal economy,” Ghanaian market traders face ongoing risk and uncertainty (see Anyidoho 2013; King 2006). Wholesalers and retailers do not know if they will get supplies to sell, particularly when goods are scarce; during an abundant harvest, unsold goods may spoil, resulting in major financial losses. The global economic challenges of recent years have exacerbated everyday uncertainties (see Horn 2010). As Nana Akua Anyidoho and William Steel (2016) show in their work on informal traders’ relationships with the formal economy in Accra, currency depreciation and rising commodity and transportation prices have significantly reduced people’s buying power in the market.

Buyers comment about the quality of sellers’ goods—whose fish aren’t quite as fresh as they used to be or who’s selling day-old bread yet claims it was just baked that morning.

Buyers who take goods on credit now struggle to repay their debts. Diminished sales not only inhibit traders’ ability to purchase goods to sell but also generate anxiety about making enough profit to cover transportation home. With limited means for business resilience, traders are at risk of catastrophic losses. A bad harvest, a market fire or burglary, sudden illness or death of a family member can instantly deprive a trader and her family of financial security—a setback from which it is difficult to recover. To mitigate these risks, traders strategically seek out trading partnerships and carefully plan where they invest their resources. Yet, they have little time for vetting prospective trading partners and supply sources. Gossip helps to shortcut this process and reduces some of these marketplace risks: it transmits useful snippets of information, indicating to traders who might prove a reliable trading partner and who they should avoid.

One day during my fieldwork in 2016, I learned that a provisions trader was nearly poisoned by one of her workers who intentionally put powdered bleach in her tea. (The trader found out and reported the young woman to the police!) On another occasion, a conflict erupted between two cassava traders near the wholesale yards, drawing a large crowd of onlookers and interveners within minutes. Leaving me to supervise her goods while she went to observe the scene, a bra seller later narrated the incident to me: a cassava seller stepped in to sell a colleague’s tubers in her absence (a common courteous practice) but sold them at a lower price than the owner desired. In uncharacteristic form, their verbal squabble escalated into a physical brawl, necessitating formal arbitration with the cassava ɔhemma (leader of the cassava traders association; see Clark 2002 on marketplace arbitration). In the hours to follow, traders discussed the incident, sharing varied interpretations of events and comments on who was culpable and the ways each violated the norms of ideal marketplace conduct.

Much marketplace gossip is not quite so scandalous, and instead comprises more mundane matters. Buyers comment about the quality of sellers’ goods—whose fish aren’t quite as fresh as they used to be or who’s selling day-old bread yet claims it was just baked that morning. Sellers complain about frugal buyers and those who have outstanding debts for goods received on credit. People also gossip about market women’s business practices—who grossly overcharges for her goods, who is stingy with her “ntɔsoɔ” (“dash” is the English translation; the complimentary extra included with premeasured quantities of foodstuffs), who measures dried goods with a dented can or one that is smaller than the standard size. (It was through the market’s grapevine that I discovered that a cooked food vendor I frequented was notorious for licking her fingers while preparing fried egg sandwiches and tea for her customers.)

A key component of business viability is a trader’s reputation—not just her reputation as an honest, reliable trader but also someone who is a good, respectful, and friendly person.

In the form of tantalizing tales ranging from the benign to the destructive, gossip—information about traders and their practices—equips market women with up-to-date knowledge about market affairs. Marketplace knowledge is also bound up with qualities of cleverness (aniteɛ/nyansakwan) and vigilance (anidahɔ/ahosohwɔ); a trader who “knows business” is not easily cheated. Because they must assess and mitigate ongoing risk and readily adapt to volatile market conditions, KCM traders harness this market knowledge to make informed business decisions.

Trading reputations

Although gossip may initially be exchanged in intimate contexts and provides beneficial information for doing business, Niko Besnier (2009, 2–3) reminds us that “gossip can nevertheless have a long reach, affect important events, and determine biographies.” At KCM, gossip can also incite economic damage and wreck personal reputations.

One day a garden eggs trader turned to me to gossip about a neighboring onion seller. Both women had spread out their produce on tarps at the edge of a busy street leading to the wholesale yards. The garden eggs seller sat on a stool, grouping the yellow and whitish vegetables into heaps of various sizes while keeping a watchful eye for prospective buyers. She occasionally punctuated our conversation with invitations for passersby to come look at her garden eggs. With the onion trader out of earshot, the garden eggs seller nodded in her direction and whispered, “That woman there, she’s not a friendly person. She doesn’t laugh or smile or call out to passersby, so don’t buy anything from her, okay?”

A key component of business viability is a trader’s reputation—not just her reputation as an honest, reliable trader but also someone who is a good, respectful, and friendly person. Reputations are built, in part, from circulating gossip—positive and negative—about past business transactions. Traders who have had positive interactions with another trader are likely to remark to others how she “really knows how to talk to people” or “knows business.” By contrast, if a trader feels as though she has been mistreated by a particular seller or customer, she may caution others against buying from (or selling to) that person. But, as Deborah Kapchan suggests in her study of Moroccan women in the marketplace, “malicious gossip is feared more than complimentary gossip is desired” (1996: 221).

In her ethnography on the role of gossip among market women in Kilimanjaro, Tuulikki Pietilä (2007) examines the “indirect dialogue” that occurs between gossipers and their targets. When “backstage” gossip reaches its target, the subject responds to criticisms indirectly. Pietilä shows how through the “semipublic sphere between the official and unofficial” women’s moral reputations and value are constructed and contested. In KCM, insinuations about a trader’s character—whether founded or not—behoove market women to avoid behaviors that may subject them to gossip. They also buffer any potential gossip by building up a positive reputation and social respectability, in part through cordial interactions with customers and colleagues and also in how they conduct themselves beyond transactional exchanges. For example, a trader who speaks respectfully and exhibits an ethos of hard work demonstrates her morality or integrity, but a momentary slip of the tongue (for example, lashing out at a customer) or a noticed absence at a social event can create lasting damage and resentment.

In Ghana’s social economy, where participation in and contribution to events such as church activities, funerals, weddings, and naming ceremonies is expected, attending a wedding or offering a monetary donation to someone during their bereavement is acknowledged and rewarded with similar reciprocal acts in the future (see for example, de Witte 2003). Failing to do so may result in serious repercussions. One trader lamented to me that a former neighbor (who is also a trader) not only failed to attend her husband’s brother’s funeral but also refused to take the funeral announcement when offered. When the latter woman found herself bereaved, the former did not attend the funeral and refused to offer any financial support.

Ghanaian traders to go to great lengths to protect, manage, and at times repair their personal and professional reputations. I witnessed such an incident at a provisions shop just outside Kumasi where I spent time after market hours and worked as an informal apprentice shopkeeper. The owner, Beatrice (a pseudonym), a widow and mother of three, stocked her store with weekly trips to the KCM.

One evening, a woman who lived in the neighborhood stopped by the shop for some insect repellent. She asked Beatrice which brands of mosquito repellent she had in stock and which she recommended. The woman settled on Sasso spray, so I stood up to get one off the high shelf. I bagged the repellent and handed it to the woman. She put the item in her purse and as she descended the steps to go home, she casually informed Beatrice that she would pay her for it the next day. Beatrice gave a simple nod of her head, but I noticed her irritation. After the woman left, Beatrice turned to me and said, “Auntie, have you seen how the business of trading is?” She complained that the woman didn’t first ask if she could take the item on credit and just assumed it would be okay (likely a face-saving strategy because she was short on cash). The incident put Beatrice in a familiar bind: When should she protect her reputation by prioritizing a customer and risk a potential financial loss? And, when should she prioritize financial security but risk an attack on her reputation, which could affect her business? As Beatrice explained, if she had refused credit to the woman or requested that next time she ask first, the woman could claim that Beatrice was just trying to disgrace her and might even go around telling other people in the neighborhood how disrespectful Beatrice is. Weighing all this in a flashing moment, Beatrice opted in favor of customer satisfaction and her professional reputation.

Lingering gossip

As the market winds down for the day, late-afternoon marketgoers gather their purchases and join congested lines forming at various trotro (public minibus) stations to wait for the next available car home. Traders pack up unsold items, sweep around their trading spaces, and calculate their profits. The day’s gains and losses invite reflection, perhaps even a recalibration of strategy. Perhaps an awkward exchange necessitates a formal apology tomorrow. Maybe a short-term loss to satisfy a customer will pay dividends. The bits of gossip transmitted during market hours linger on in the minds of market women as they prepare for another day of buying, selling and talking their trade.