Article begins

The landscape of Islam within China has been changing rapidly during the pandemic. Ethnographic fieldwork can map these erasures and disappearances in everyday life.

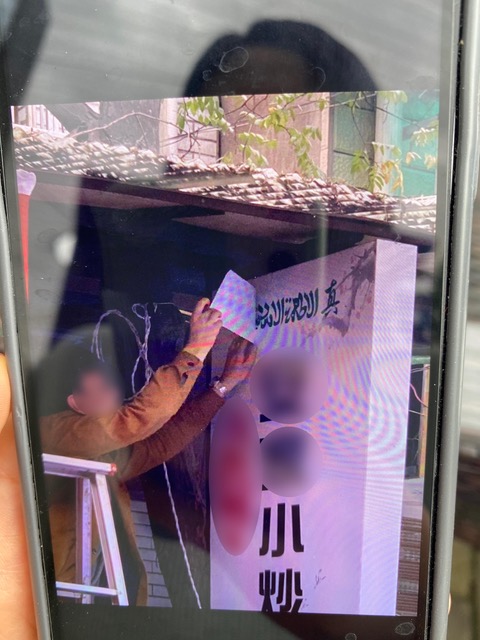

It was an unusually quiet Ramadan in the Muslim Quarter, also known as Huifang, in the ancient city of Xi’an, China. All mosques were closed due to the government’s COVID-19 regulations. Handwritten posters indicated that they had been closed since the lockdown of Wuhan in late January 2020. But most restaurants were already open when I arrived in Xi’an in early May. My friend Tao, a local Hui resident, picked me up with his small electronic motorcycle near the Bell Tower and treated me in a noodle restaurant close to his house. When enjoying a bowl of delicious beef noodle, I noticed one thing: the halal (qingzhen) signs in Arabic and English were all gone. Some were obviously crossed out by black stickers or markers and some were covered with a sticker of a lotus sign representing the district’s name. Moreover, some Sino-Arabic calligraphy on the walls of some restaurants also disappeared. Two days later, when I met with Old Ma, a knowledgeable local Hui scholar, and asked him about the halal signs, Old Ma pulled out his cellphone and showed me some photos of halal signs taken in November and December of 2019. “Look, things can disappear really fast.” Knowing me as an anthropologist, Old Ma insisted, “When you see [them], record first and then write” (ni kanjian le, xian ji xialai, yihou zai xie).

Image description: A man stands on a ladder under an awning, applying what looks like a large sticker to cover the green Arabicwriting on a restaurant shop sign. The remainder of the sign, in Chinese, remains visible.

Caption: A photo of Old Ma’s phone screen, showing a man covering up the Arabic on a sign in 2019. Jing Wang

Inspired by my interlocutors like Tao and Old Ma, I have come to realize, perhaps more than ever, a renewed sense of urgency to see ethnographic fieldwork as a method of “witnessing” in the times of pandemic. Writing about political lying during the Trump administration, Carole McGranahan suggests that anthropology provides an opportunity to record and document erasure. “When you see [them], record first and then write” is not just a simple piece of advice out of Old Ma’s personal concerns. It is also a timely invitation to rethink our current mode of anthropological knowledge production through what Gökçe Günel, Saiba Varma, and Chika Watanabe term patchwork ethnography and the value of witnessing, recording, and archiving.

COVID-19 has become a convenient excuse for closures, silencings, and disappearances in China. In a landscape of fast disappearance and emergence, Old Ma’s comment finds its resonance both within and beyond Muslim communities. For instance, Chen Qiushi, a Chinese lawyer and citizen journalist who covered the Hong Kong protests in 2019 and the early coronavirus outbreaks pandemic in Wuhan, disappeared in early February 2020. The public mourning over the death of Dr. Li Wenliang, a whistleblower of the early outbreaks in Wuhan, was quickly silenced in cyberspace and other public spheres in China.

While the disappearing of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang had already elicited unspoken fears among the Hui Muslim communities across China before the pandemic, their fears and worries over the disappearance of the Islamic signs and spaces across Northwest China have certainly intensified during the pandemic. Since 2018, the state work of de-Arabicization has already taken effect among the Hui Muslim communities in China. The taking down of the Arabic halal signs in restaurants is just one example. Another visible change has been the demolition of mosques such as the Weizhou Grand Mosque in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region in 2018. While the Weizhou Mosque was spared from a total demolition thanks to the local resistance, it has nevertheless become sinicized during the 2020 pandemic. The onion-shaped dome has been replaced by a Chinese-style dome in the name of “renovation” (gaizao). The term renovation in this context is problematic because it aims to sinicize and uniformize the architectural style of mosques. This said renovation work has quietly impacted almost all the Hui communities I visited during this summer. For those mosques still yet to be renovated, a few local Hui friends commented, “It’s just a matter of time” (zaowan de wenti).

Image description: A mosque building is wrapped in green netting and scaffolding, and a construction crane is visible behind it. The sky is dark.

Caption: A mosque in Linxia, Gansu was under “renovation.” The dome was gone when the picture was taken. Jing Wang

Indeed, time becomes a key element in the quiet yet rapidly changing landscape of Islam in China. The Arabic halal signs, onion-shaped domes, and tall minarets do not disappear overnight. The task of renovation could take several months, half a year, or over a year to finish. The demolished remnants take time to disappear. A large-sized dome could be sitting in the open next to a mosque without a dome for a long time. A small crescent moon symbol on the top of a dismantled dome could be easily hidden away in the storage room. It also takes time for local communities to absorb the disappointment, anger, fear, confusion, and uncertainty during the unpredictable timeline of renovation work. To witness, for people like Old Ma who always takes a camera wherever he goes, is to record and archive the disappearing landscape in one’s own community.

Time has become patchy not just for my interlocutors who witnessed the disappearance of their familiar signs but also for me who carried out patchwork ethnography to observe such disappearances. Particularly through my field visits in 2020, patchwork ethnography offers a rich toolkit for me to adjust the rhythm of fieldwork contingent on the unpredictability of the pandemic situations. Travel restrictions began to loosen in early May in China; yet each province, city, town, or even village might have their own pandemic restrictions. When the summer approached, I needed to coteach a summer school course with my colleague in Shanghai for six weeks. Besides, the losses of two family members over the summer made it particularly difficult to travel.

Image description: A large blue-green, onion-shaped dome that would normally be seen on the top of a building, sits on a lawn ,surrounded by grass and trees. There appear to be a few pieces missing from the dome’s surface. Behind the dome is a row of high-rise residential buildings.

Caption: A green dome was sitting on the lawn outside a mosque in a small city between Gansu and Qinghai. Jing Wang

As Günel, Varma and Watanabe put it, patchwork ethnography “begins from the acknowledgement that recombinations of ‘home’ and ‘field’ have become necessities” and is “an effective, but kinder and gentler way to do research.” Indeed, by acknowledging the difficulties of “being productive” at all fronts, the method of short-term field visits liberates me to concentrate on one thing at a time without pushing myself too far. It also allows me to be more sensitive to witness and record the recurring phenomena, emotions, and discussions through multiple visits. Between early May and late August, I conducted several short field trips in Shaanxi, Gansu, Ningxia, and Sichuan, some of which partially overlapped with Ramadan and Eid al-Adha. One trip lasted about a month and another three ranged from five days to two weeks, conducted under COVID-19 precautions. Finding effective masks, constantly checking health codes, and keeping proper social distance all become part of patchwork ethnography. It is during those short visits that my interlocutors repeatedly reminded me of the importance to witness and record what has been quickly disappearing across different locations.

How to bear witness, record, and archive a landscape of disappearance requires a rethinking of our modes of doing our work. Indeed, anthropologists have long been working to document disappearing worlds. As Ruth Behar puts it, “Anthropology is the most fascinating, bizarre, disturbing, and necessary form of witnessing left to us at the end of the twentieth century.” While Behar’s 1997 work focuses on death, memory, return, and the “vulnerable” self as the observer, in the time of a global pandemic like COVID-19, the value of ethnographic fieldwork as a form of witnessing has become increasingly important, especially when many things are disappearing at an alarming rate. Moreover, the possibilities of conducting fieldwork have been further challenged by the varying quarantine rules, travel restrictions, funding scarcity, internet accessibility, housework, and concern for interlocutors and one’s own health, among other factors. Zeng Yukun’s discussion of homework and fieldwork, in which he wonders “to what degree these COVID-19 reflections privilege our own experiences and recreate an anthropological fetish of anything new” resonates with my work and experiences. Rather than pursuing the new, it is paramount to take the lead from our interlocutors and reevaluate the importance of witnessing the now and the disappearing. Anthropologists have long realized how anthropological knowledge production can be both deeply disturbing and yet critically important. It still holds true, perhaps more so, in a time of public health crisis when governments around the world exert more influence over social life.

Jing Wang is a Global Perspectives on Society Postdoctoral Fellow at NYU Shanghai. She earned a PhD in social/cultural anthropology from Rice University in 2019. Her research focuses on diversity and racial/ethnic equality, critical race and ethnic studies, anthropology of Islam in China, diasporas, global histories of Silk Road, media, and qualitative methodology.

Hanna Pickwell and Elizabeth Rodwell are section contributing editors for the Society for East Asian Anthropology.

Cite as: Wang, Jing. 2021. “Witnessing Disappearance in China during the Global Pandemic.” Anthropology News website, March 31, 2021. DOI: 10.14506/AN.1611