Article begins

In the last few years, Italy has experienced anti-Semitic, racist, and homophobic episodes, fueled by the xenophobic rhetoric and provocations of politicians like Matteo Salvini, head of the far-right party of The League (La Lega). In response to this right-wing populism, the “Sardine” movement was born in the weeks leading up to the regional elections in Emilia-Romagna and has gained traction both in Italy and abroad. What are the semiotic and ideological characteristics of this fish-inspired movement? And will it have a legacy within the broader landscape of political and civic activism?

The origins of a (fish) movement

Soon, both factions realized that they would have to reckon with a new force on the political horizon: the “Sardine” movement.

In 2018, Italy became the first European country ruled by a right-wing populist government, emerging from a coalition between The League and the anti-establishment Five Star Movement. Thanks to a successful mobilization of Euroskepticism and white nationalist anti-immigrant rhetoric, the League won 33.4 percent of the vote in 2019. Its leader, Matteo Salvini, drew on other brands of Italian populism (such as Berlusconi’s billionaire populism or Beppe Grillo’s f— you politics), showing up as a hypermasculine leader who unabashedly challenged liberal do-gooders (buonisti)—be it by turning away refugee rescue boats in the Mediterranean or by sharing the stage with neo-fascist organizations such as Casapound. Thus, when the political coalition broke down in the summer of 2019, Salvini asked for new elections, hoping that Italians would grant him “full powers” to govern the country—a statement with deep fascist and authoritarian undertones. Yet, much to Salvini’s chagrin, Italian voters did not return to the polls. Instead, a new center-left coalition between the Five Star Movement and the left-wing Democratic Party (PD) took hold, pushing The League to the opposition.

Salvini thus turned his efforts to the January 2020 regional elections, hoping to achieve a landmark victory in Emilia-Romagna, a historically leftist bastion. The region’s standing left-wing president Stefano Bonaccini launched his reelection campaign in the last months of 2019. Meanwhile, Salvini began touring the region in support for Bonaccini’s main opponent, the right-wing candidate Lucia Borgonzoni.

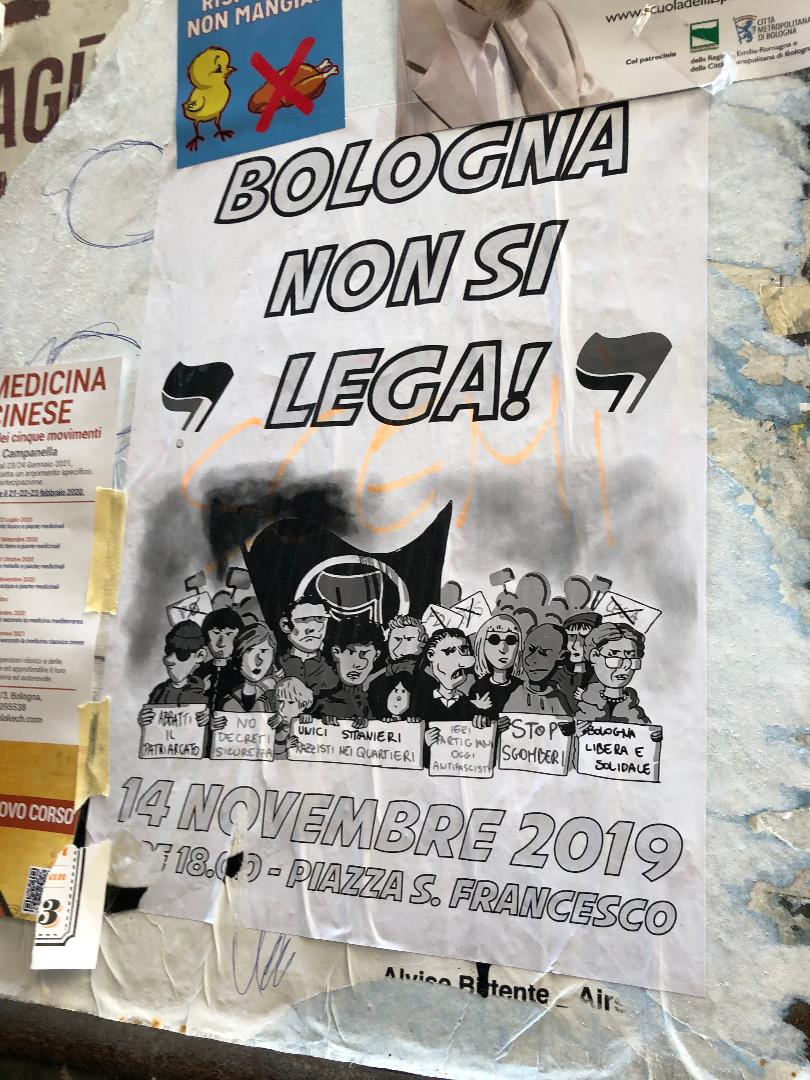

Image description: A flyer is pasted on a wall atop older, faded and ripped papers. The edges of other flyers are visible beside and above it. On the flyer, there is a black and white illustration of a diverse group of people holding banners and protesting. The text on the flyer reads “Bologna non si lega!” at the top, and at the bottom it reads “14 Novembre 2019, Piazza S. Frencesco.”

Caption: Flyer in Bologna advertising an anti-League and anti-fascist protest in November 2019 with the “Bologna non si lega” message. Sahar Yazdani

Soon, both factions realized that they would have to reckon with a new force on the political horizon: the “Sardine” movement. As Salvini made his first appearance in Bologna on November 14, 2019, thousands of people crowded the main square of Piazza Maggiore to proclaim through wordless fish-shaped signs that he was not welcome. This fish-inspired protest stemmed from a Facebook post that four individuals in their thirties had circulated on social media a few days earlier. The post challenged 6,000 people—the same amount that could fit in the venue where Salvini’s assembly was held—to “pack like sardines” in Bologna’s central square and “join the first ittic [fish] revolution in history.” The rules of the event were simple: no flags, no party symbols, and no hate speech. A surprise to most, more than 12,000 people showed up in Piazza Maggiore. The crowd gathered voters of all ages and backgrounds, all united under the slogan “Bologna won’t bite” (“Bologna non abbocca”).

Although the Sardines never openly supported Bonaccini’s electoral campaign, the event had a high showing of leftist collectives and left-leaning civil society organizations. This was, in essence, an explicit manifestation of dissent against The League’s fascist tendencies and fearmongering tactics. In the following weeks, the protest grew into a decentralized movement. People from all over Emilia-Romagna announced that their towns would also not be “tied”—a wordplay on the name The League, Lega, which literally means “to tie”—and organized dozens of local flash mobs in their cities. Soon, protests spread outside the region: newborn groups of Sardines launched “fish” mobs in Milan, Turin, and Rome, and among Italian expats abroad.

Image description: A plaza is filled with a crowd of people, all standing shoulder-to-shoulder. Many people in the crowd hold sardine-shaped signs. A large blue banner stretches across a portion of the crowd with white text reading “Bologna non abbocca.” Two cream-colored buildings stand on two sides of the plaza.

Caption: Banner exhibited during the Sardines’ first gathering, “Bologna non abbocca,” November 14, 2019. (CC BY 2.0)

The humble sardine as a symbol of collective resistance

The Sardine movement has been described as “one of the most visible examples of anti-populist mobilization in Europe.” But why was this fishy metaphor so effective in conveying these ideals?

The sardine is the opposite of a haute-cuisine ingredient: it is the proletarian fish par excellence. Sardines are small and vulnerable so they move in large schools. When turned into a consumption good, sardines become compressed together in a tiny tin can. The expression “packed like sardines,” hence the name of the movement, has a symbolic valence that translates into the act of filling public squares.

The Sardines proudly embrace the values of humility and vulnerability indexed by the fish, seeing them as the force that binds people together and enables them to stand in solidarity against far-right extremist attacks. This symbolism is further amplified by the movement’s inclusive messaging (“Anyone can be a Sardine!”), and by the do-it-yourself, wordless aesthetic of its signs.

The efficacy of this fish symbolism was unintentionally proven when, shortly after the first gathering in Piazza Maggiore, League politicians circulated images with sardines being eaten by kittens and pigs on social media, mocking the symbol for provocation. This kind of aggressive messaging contrasted with the “language” adopted by the movement which, as declared by the four original organizers, is one based on “nonviolence, creativity, and listening” so as to include a “plurality of voices.”

Image description: In the foreground, a sardine-shaped sign made out of cardboard, decorated with black, green, and silver colors. In the background, a crowd of protesters carrying smaller sardine-shaped signs that lighten up in the dark.

Caption: Sardine-shaped signs at a flash mob in Verona, Italy on November 2019. Roberto Spagnoli

The Piazza, the cornerstone of Italian public life and political struggle, is the Sardines’ center stage. Echoing the strategies and decentralized networked structures of global grassroots protests (such as those in Hong Kong and Chile), the Sardines proclaim to be an inclusive leaderless group: a “formless” multitude ready to crowd piazzas and voting booths, harnessing political participation as a fundamental value. In the “open sea” (mare aperto) of piazzas, “old commies” can be found swimming next to young people disenchanted with Italian politics: no one is left out of the school (fuori dal banco) or unprotected from populist attacks.

By leveraging the unifying power of the multitude in their messaging, The Sardines thus turn the “us vs them” right-wing populist rhetoric on its head. Adopting a quiet style of political protest, the movement harnesses the aural and semiotic properties of a “mute” fish to fight the boisterous claims of politicians like Salvini.

Bigger fish to fry

In January 2020, 67.7 percent of voters in Emilia-Romagna went to the polls, a 30 percent increase from the preceding regional elections of 2015. The center-left candidate Bonaccini won with 51.42 percent of the votes, while Borgonzoni trailed with 43.63 percent. Bonaccini’s party, the PD, publicly acknowledged the role of the Sardines in increasing voter turnout and helping their candidate’s reelection. But whether this “fish activism” can create everlasting change remains to be seen.

The sardine is the opposite of a haute-cuisine ingredient: it is the

According to some, the Sardines’ refusal to participate in electoral politics will inevitably determine their fizzling away—or worse, their cooptation by private business interests. Regardless, Sardines have already changed the seas in which they have swum. They unexpectedly galvanized the center-left’s electoral campaign, an increasingly tall order in Italy and Europe. The Sardines’ inclusive messaging also enlivened grassroots initiatives across Italian cities, especially among younger generations. Some UK and US observers have commented that there are lessons to be imported across the English Channel and the Atlantic in challenging right-wing populism.

Moreover, as the sardine’s symbolism has outlived the Emilia-Romagna political campaign, it seems as if the fish is an unlikely expression of collective resistance to right-wing populism. While the movement was originally based on mass public participation, its symbolism survives despite current obstacles to public assembling.

In March 2020, when Italy was subject to restricted lockdowns due to the outbreak of COVID-19, the Sardines used “virtual piazzas” to cultivate empathy and solidarity at a time of social distancing. These values have acquired a new salience in the current moment, as have the experiences of discrimination and social and cultural isolation that the movement was trying to address.

When the lockdown is over, the Sardines will restart organizing, assembling, and packing in virtual and physical piazzas across Italy using animal symbolism to reclaim the values of anti-fascism, inclusion, and civic participation at a critical moment in Italian history.

It might sound fishy, but it also might work.

Livia Garofalo is a PhD/MPH candidate in the Department of Anthropology at Northwestern University. She is currently completing her dissertation on the nexus between biomedical urgency, injury, and socio-economic crisis in public intensive care units in Argentina. She can be reached at [email protected] and on twitter at @livgar.

Elisa Lanari is a cultural and urban anthropologist researching inequality, racism, migration, and “city” making in the US South and Italy. Her work on suburban gentrification has recently appeared in City & Society. Elisa is currently a visiting researcher at IUAV University of Venice, Italy. She can be reached at [email protected] and on twitter at @ElisLan.

Martina Cavicchioli is completing a PhD in social and cultural anthropology at the Goethe University of Frankfurt in Germany. Her research explores risk assessment and choices in agriculture in areas of Burkina Faso affected by land degradation from a gender perspective. She can be reached at [email protected].

Luzilda Carrillo Arciniega and Chandra Middleton are contributing editors for the Association for Political and Legal Anthropology’s section news column.

Cite as: Garofalo, Livia, Elisa Lanari, and Martina Cavicchioli. 2020. “Sounds Fishy?” Anthropology News website, September 10, 2020. DOI: 10.14506/AN.1487